Coal Industry Deep Dive Part 1: Calculating the Externalities

If you’re reading this, you likely don’t need any persuading that coal is bad – bad for the environment. For the climate. For miners. For human health. Catastrophically bad.

This may seem obvious to us, and it might look like coal is on its way out. But it’s not there yet. Sure, there are frequent news reports about old coal mines closing (with some even becoming large solar farms), but coal, and the money it makes, still exerts a powerful hold on the world.

Imagine you’re talking to a banker for whom coal still means pots of money. Why bother looking for alternatives? In Australia and Wyoming and West Virginia, Coal Remains King. (Kind of. Wyoming’s coal industry accounts for 40% of the US total output and as recently as 2014 this drpve14% of the state’s economic activity, contributing $1.3B to the State’s government revenues, 11% of totals. With coal plants across the US shutting down, coal production was “in freefall” dropping from 400M US tons / year in 2014 to under 250M in 2023.) And China burns more coal than anyone - even as they accelerate their awesome deployment of thousands of hectares of solar panels. India’s economy, on a growth tear, is largely coal-fueled. Coal is (still) profitable. And bankers, policymakers, and industrialists don’t make decisions based on words like “good” or “bad.” They make decisions based on $B, or €B, or £B, or ¥T.

So just how bad is coal? The answer to that depends on how and what you count and what type of coal. But here’s a brief summary of the good, bad, and worse impacts of coal.

In this paper, we’ll deal with the most obvious, and pressing, of the external harms from coal: the vast damage to the earth’s atmosphere and specifically the climate. We use our own calculations, but compare these to calculations from the International Monetary Fund, and others. In subsequent papers, we’ll review the external harms from non-climate damage to the natural environment, to human health, and to other aspects of human life. We will then summarize the total externalized costs of coal, and we’ll look at solutions and possible actions we can each take to accelerate the end of coal.

Coal’s climate harms by the numbers

First, we want to show you, in detail, that the data we use is of high quality and that our analyses are correct. We show that there are ranges, and that different sources give different, and sometimes wildly divergent answers. Let’s look at the Scope 3 (in use) harms caused by the CO2 emissions of burning coal.

How much coal is sold per year? Per the IEA: Coal consumption in 2022 rose by 3.3% to 8.3 billion tonnes (A tonne is a metric ton: 1,000 kilograms. That’s 2,204 pounds – 1.10 US tons and 0,98 UK tons. Since these are within a few percent of each other, and metric units are standard for this calculation, we stick with tonnes.). It’s rising still.

- Gulp! At wholesale, US power producers buy coal for $45/tonne, while the international price for high-quality coal reaches about $120/tonne. So, $600B to $996B in 2023 – we’ll settle on $800B as a useful average. This is slightly under 1% of the whole world economic activity total of about $100T in 2023. You can see why bankers don’t want to kick the coal habit.

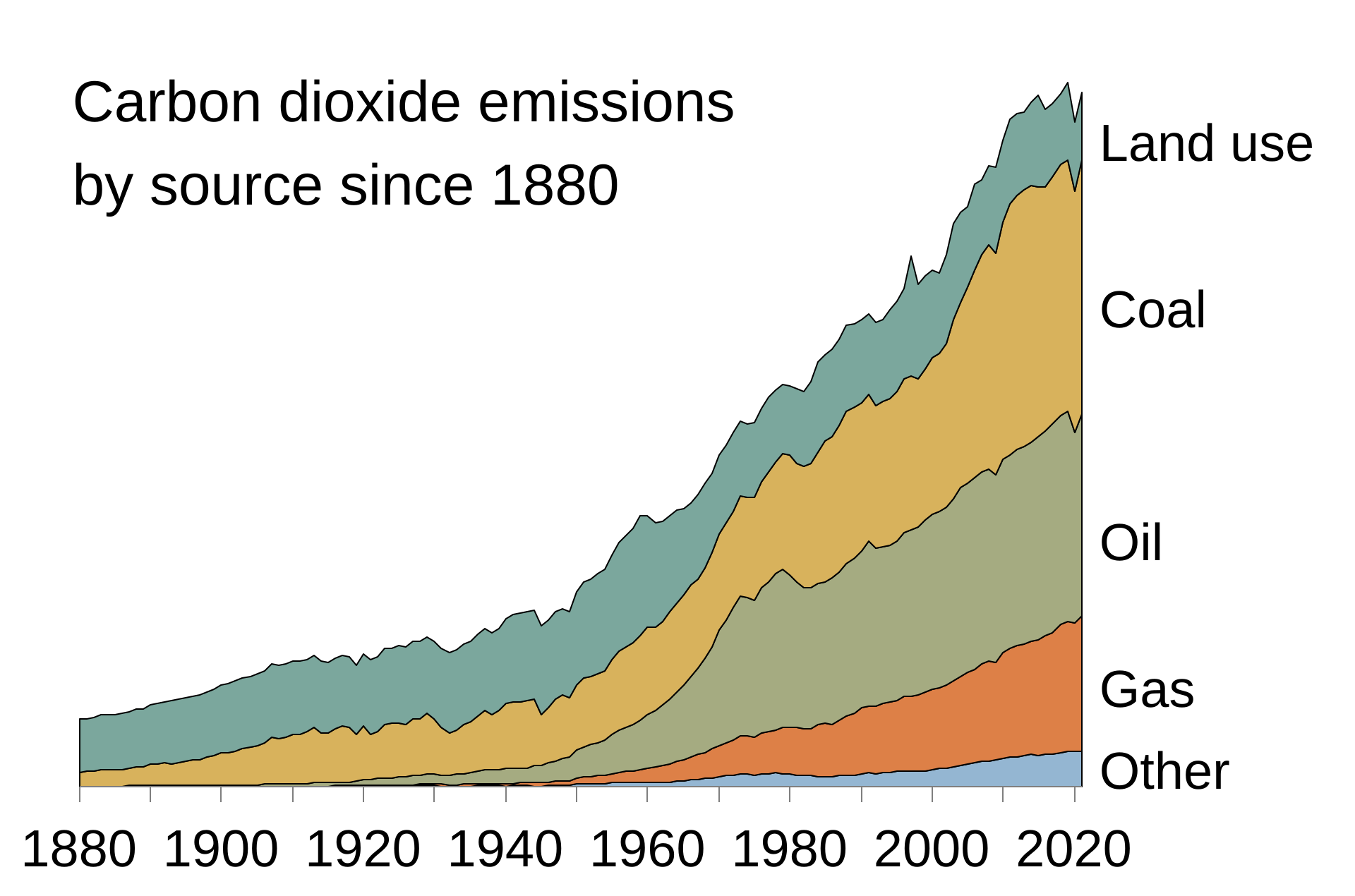

- How much CO2 is created by burning coal? It may seem counter-intuitive, since coal is solid and CO2 is gaseous, but in practice, burning a tonne of coal yields at least 2.1 tonnes of CO2. The reason is based in simple atomic chemistry. it’s easy to understand burning coal as oxygenation of carbon. The chemical reaction C + O2 = CO2 involves a 12-atomic mass Carbon atom bonding with two 16-atomic mass Oxygen atoms to create a 44-atomic mass CO2 molecule, implying a 44/12 ratio: 3.66. In practice, combustion’s not 100% efficient, and coal isn’t really pure carbon, plus some is lost as dust along the way, etc. When oil or methane burn, “it’s mainly the [chemical reactions around the hydrogen atoms] that generate energy, not the carbon atoms.” Given the total annual consumption of coal —8.3BT—and assuming it all gets burnt in the current year, coal contributes 17 billion tonnes of CO2 per year to the atmosphere – an astounding 45% of the global total of 37BT/year. Our estimate is similar to the estimate depicted in the Wikipedia graph here:

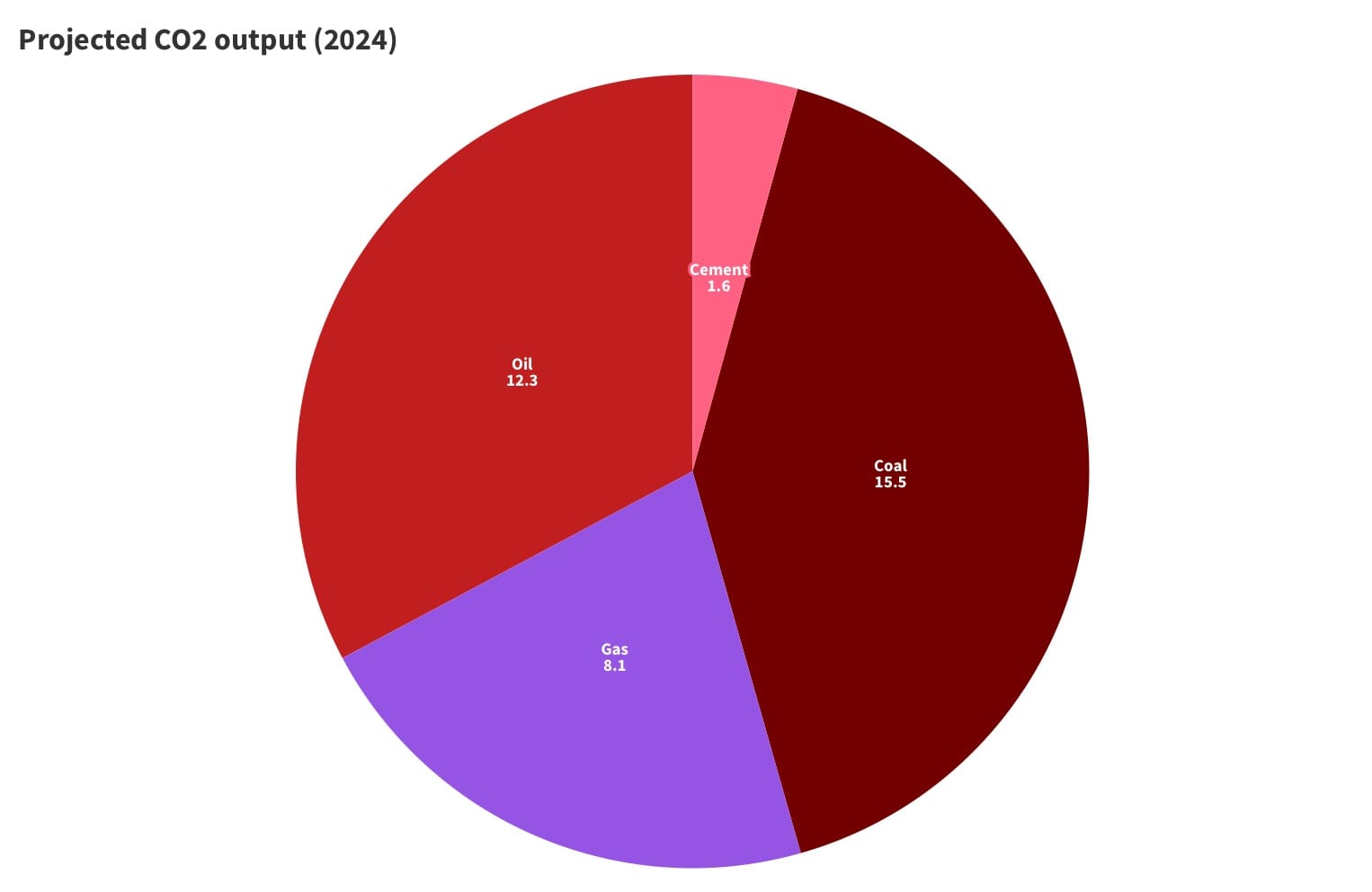

The IEA offers a slightly lower estimate of total greenhouse gas emissions from coal and peat and oil shales at 15.1GT/year - 44% of the total it calculates for combustions of fuels. And CICERO, the Center for International Climate Research in Oslo, shows coal’s contributions at 15.5GT in 2024, as depicted in the graph below:

Either way, it’s clear that the single largest contributor to GHG, and to climate damage, is coal. The most important thing humanity can do to minimize future damage is to shut down coal as quickly as possible.

Given the unarguable data that the growing burden of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is creating an existential threat to humanity, there is a vast and diverse body of analyses looking at the costs of climate data, some of which tie back to an imputed cost per ton of CO2. There are complex ways of calculating the contribution of coal and there are simple, useful ways. Here are two of the latter, and be warned, while they’re simplified summaries, there’s a lot of numbers to be digested:

- Cost of sequestration: The US government Congressional Budget Office 2023 report on carbon capture offers this summary: the cost to capture one tonne of CO2 using direct air capture (Direct Air Capture refers to capture from the general atmosphere, not at point of emission) ranges from $135 to $345, compared with $15 to $120 for Carbon Capture and Storage (capture of CO2 at point of emission) in various industrial settings. Because DAC is a more experimental process than CCS, estimates of its costs are more uncertain. Other analysts estimate that costs are likely to be much higher — $600 to $1,000 per tonne, or more — over the next decade. Whereas the CBO office report mostly looks at industrial processes for carbon capture, it is estimated that the cost to sequester a tonne of CO2 from the air using extension of natural means (extending and maintaining a forest) could be as low as about $45/tonne. In a terrifying and grave development, though, the role of lush forests as carbon sinks is being diminished by human activity – and by the effects of climate change itself.

"The global forest sink is equivalent to almost half of fossil-fuel emissions ... However, two-thirds of the benefit from the sink has been negated by tropical deforestation. Although the global forest sink has endured undiminished for three decades, despite regional variations, it could be weakened by ageing forests, continuing deforestation and further intensification of disturbance regimes. To protect the carbon sink, land management policies are needed to limit deforestation, promote forest restoration and improve timber-harvesting practices.”

- Since each tonne of coal creates 2.1 tonnes of CO2, the sequestration costs can be estimated in the range from $90/tonne of coal — using the forest-extension cost as the low bound — to $420/tonne of coal at the high end,— assuming $200/sequestered tonne near the middle of the DAC cost range.

- Existing rules: The social cost of carbon. There is extensive work estimating the climate costs associated with CO2 passed into the atmosphere. One recent, thorough analysis suggests $185 per tonne of CO2 in 2020 dollars, which implies perhaps $220/tonne in 2024. Back-calculation from this to tonnes of coal burnt we get a climate cost of $95 tonne of coal.

- Most analyses of the Social Cost of Carbon center on Climate Damage, as for instance the US EPA draft report from 2022 which, as do most analyses, consider climate-damage assessments, the Roosevelt Institute analyses – which centers on mitigation costs. All of these point to ranges close to $100 / tonne, but we freely acknowledge that some slightly lower numbers and some considerably higher estimates can be supported. In a notable lawsuit nearly a decade ago, a coal company argued for social costs well under $5/tonne - and lost, while estimates then of $11 to $57/tonne prevailed. Subsequent analyses repeatedly point for far higher costs.

- Again, recall that each tonne of CO2 in air corresponds to 0.48 tonnes of coal burnt, so considering damage consequent to burning a tonne of coal requires us to multiply the in-air cost/sequestered tonne by 2.1.